Close Protection

CLOSE PROTECTION SETTING THE SCENE: It is the premiere of a much-publicized movie. A large crowd of excited fans, holding autograph books and associated memorabilia has gathered on either side of the red carpet, anxiously awaiting the arrival of the stars. Media and photographers have gathered around the entrance to the theatre.

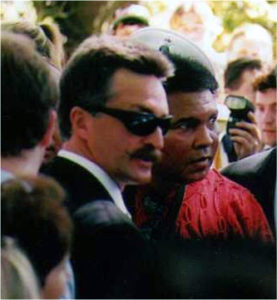

Hans Van Beuge is leading a close protection protective detail, tasked with the safety and security of one of the stars of tonight’s event.

The security team has planned and prepared extensively as, according to Van Beuge, this is the time the client could be at greatest risk.

Finally, the last stretch limousine arrives at the red carpet. After giving final instructions to the driver, Van Beuge is the first to exit the vehicle. He scans the crowd carefully and makes eye contact with advance agent Scott Agostino, who has been on site for several hours already. Agostino has been assessing the crowd as they arrive with the intensity of a lifeguard watching swimmers in the water.

He gives a nod to Van Beuge who then opens the rear door of the limousine and escorts his client onto the red carpet. The walk into the theatre has been carefully choreographed. The movements between the protectee and protectors have been meticulously synchronized.

It is imperative that the security team achieve a balance between maximum exposure for the celebrity and minimum security risk; a goal which they achieve with the easy grace of seasoned close protection professionals.

Van Beuge knows that from a threat management perspective, award nights and premiers have inherited weaknesses. Due to the publicity surrounding these events, any individual who has inappropriate intentions towards their clients knows exactly where they will be at a specific time. He is aware of the need to be extremely well-prepared and vigilant.

On previous such occasions, Van Beuge has had to manage stalkers attempting to make contact with his clients as well as protesters and serial pests trying to cause embarrassment or gain publicity at a celebrity’s expense. In all these instances, early identification and intervention has neutralized any potential confrontation.

According to Van Beuge, the mentally disordered individuals who engage in pursuit behaviors (Van Beuge’s preferred term for “stalking”) that cause him the most concern. To counter these threats, Van Beuge relies on psychology as much as traditional security methodologies to provide effective protection.

“The greater our understanding of people who engage in pursuit behavior, the better our chances of predicting what they may do and then implementing preventative measures,” says Van Beuge.

The Rise in Celebrity Stalking and Media Exposure Increases Need for Close Protection

According to Van Beuge, there are far more cases of celebrity stalking that are reported in the media. Many cases go unreported to law-enforcement agencies. Most famous public figures don’t want the publicity associated with these cases. Instead, they rely on private sector specialists qualified to manage their close protection deal in a more subtle manner.

Van Beuge says he believes there are biopsychological factors associated with stalking behaviors, and that there has been a massive increase in celebrity stalking over the past 30 years.

He cites research in the United State that claims over 30% of the population is affected by what can be called a Celebrity Worship Syndrome to some degree, or CWS has been described as “an obsessive-addictive disorder where an individual becomes overly involved and interested (i.e., completely obsessed) with the details of the personal life of a celebrity.

Any person who is “in the public eye” can be the object of a person’s obsession (e.g., authors, politicians, journalists), but research and criminal prosecutions suggest they are more likely to be someone from the world of television, film and/or pop music.” (Mark D. Griffiths, Ph.D., Psychology Today)

For most people, it is just a fascination with the lives of the rich and famous. They follow the news of celebrities in the media for entertainment or social reasons. However, in its most intense form, celebrity worship syndrome can affect about 1% of people who develop borderline pathological conditions.

Van Beuge says that the media has played a major role in the increase of celebrity stalking. Imagine what it’s like for those people who have difficulty separating reality from fantasy, having a celebrity seemingly talking directly to them out of a television set in their own home.

Television creates a feeling of intimacy for some people. Look at the large number of interview and gossip shows and the huge range of magazines that are devoted to celebrities and their lifestyles. People are likely to know more about their favorite celebrity then they do about their next-door neighbor.

John Ellery, one of Australia’s leading Hostile Environment Specialists and a former SAS Counter-Terrorist soldier, agrees on the value of Van Beuge’s study of psychology as an aid to understanding violent behavior.

According to Van Buege’s research, unwanted pursuit behavior is the result of a mental illness. Someone who is mentally ill may develop delusions related to anything that is within their environment. Television brings celebrities and their private lives into that environment.

Combine this with a general increase in mental illness and a decrease in effective treatment for the mentally ill, and you have a situation that gets worse by the day for famous individuals, who are becoming increasingly dependent on close personal protection.

Close Protection Check List: Factors in Determining and Deterring Pursuer Behavior

Van Beuge believes the two most important factors in determining whether a celebrity unwittingly draws a stalker are: How many people know about the celebrity (how famous is he/she?) and secondly, how approachable does the celebrity appear to be?

Celebrities who are perceived as nice, friendly, approachable and non-threatening are likely to have more problems. The disordered pursuers who seek relationships with celebrities are drawn to those who seem less likely to reject them.

Van Beuge cites six types of situations where unwanted pursuit behavior may occur:

- An individual can be deluded in the belief that another is in love with him or her, despite evidence to the contrary (erotomania)

- An individual is strongly attracted to another and pursues him or her to gain attention (love obsessional)

- An estranged spouse or lover refuses to be rejected (rejection- based)

- A current spouse or lover has delusions of jealousy with respect to his or her partner

- Individuals in business or social relationships seek revenge for a perceived wrong (revenge-based)

- A serial sex offender or murderer stalking a potential victim as part of his planning process (sociopathic-based).

The Erotomaniac Stalker

According to Van Beuge, the erotomaniac stalker is the one most likely to pursue a celebrity or famous person. In their delusional state, they believe that the victim is in love with them. The Erotomaniac receives what is clinically known as ego-syntonic messages from the victim.

They believe they are getting personal communications directly from the celebrity when they sing a song or appear on screen.

Celebrities often receive a huge amount of fan mail and some of it comes from these types of pursuers. Van Beuge explains that while receiving threatening or inappropriate communications can be very distressing for a celebrity, only about 10% of pursuers who send inappropriate material will actually attempt an encounter with their victim.

However, of those who attempt a face-to-face encounter, approximately 70% have previously written or phoned the celebrity before-hand.

Van Beuge points out that this is good news because these individuals usually give advance notice that they are going to be a problem. So the first line of defense for the close personal protection detail is in monitoring all unsolicited mail, phone calls, e-mails, cards and gifts that are received by the client.

It is crucial to identify, investigate and assess these items. There are about 40 factors that are “red flags” in communications, things considered to pre-cursors of behavior that may be dangerous to the client’s well-being.

Van Beuge explains that he reviews about 300 items a month for his clients. When there is a concern, they investigate the individual who sent the item. On a positive note, he says research shows that people who send threatening letters to a celebrity are statistically no more likely to try and approach them than those who write them love letters.

It’s important to remember that behavior that is based on fantasy is very likely to escalate, so it is foolhardy as a close personal protection operative to assume that only a letter that sounds threatening should be reported to the authorities. The love letters could be problematic too—possibly more so.

Observation & Restraint Key in Close Protection

How a stalking or unwanted pursuing incident is case-managed can also impact on its level of severity. Van Beuge recommends treading very lightly at the start. He always tightens the physical protection of the client but usually investigates the pursuer in a surreptitious manner, working towards containment rather than confrontation.

Confrontation, according to Van Beuge, can often incite more extreme behavior. Seeking restraining orders or reporting the activities of a stalker to authorities may escalate the risk for the victim. These courses of action can be perceived by the mentally ill stalker as a challenge which can increase their anger.

The goal is not about achieving a conviction for the pursuer, it’s about achieving a safe conclusion for the client. The two are often not compatible. Only a very small number of stalking cases end in violence.

Stalkers usually don’t want to hurt the person they are pursuing–they want to form an attachment. According to Van Buege, it manifests as a methodical, ongoing intrusiveness, and he just keeps reading the letters and monitoring their movements.

It can go on for many years, but as long as the behavior isn’t dangerous to the client, he is satisfied his team is providing appropriate close personal protection.

When violence occurs, it is usually because the pursuer realizes that their fantasy is not going to happen, resulting in cases where there may be either an explosion or implosion of violence, such as homicide or suicide.

In the course of his work as a close personal protection specialist, Van Beuge has dealt with several cases where pursuers have become suicidal. In these instances, he has liaised closely with psychotherapists and other mental health professionals, and if possible, the pursuers family, to achieve a safe solution for the offender.

The bottom line is that these individuals should never be allowed direct contact with the client, according to Van Beuge. He urges everyone in the close protection field to research and explore psychology. He believes that in order to effectively protect your client, you need to be an acute observer of human behavior. “You will never work out the solution to a problem if you don’t understand it in the first place,” he cautions.

BACK AT THE PREMIERE: Van Beuge escorts his client out of the theatre fifteen minutes before the conclusion of the event.

The publicity requirements having been satisfied at the start of the evening, Van Beuge now utilizes the anonymity of the darkness and the emergency exit to take his client to the repositioned limousine. Van Beuge and his client travel away from the theatre before the house lights have come on.

Agostino has advanced the after-party and is waiting with venue security to meet them at the rear door of the crowded nightclub. In this tightly packed environment, they will balance the client’s need to enjoy the party whilst maintaining privacy.

By the time the party is over, Van Beuge will have completed a 21-hour shift. This is the life of a close protection specialist. In four hours, he will escort his client to the film set, where he will spend another day managing his client’s safety, assessing fan mail, liaising with studio security and film safety officers and pre-planning his clients after work activities.

This article was written by John Bigelow