Soldiers Magazine, by Lisa Gregory

THE Army chief of staff leaves his vehicle and safely enters a building somewhere in the world. Before this simple act can occur, agents from the Department of the Army’s Protective Services Unit must plan and coordinate the trip, conduct a threat assessment, tour the routes and the destination, and conduct motorcade operations to ensure the dignitary’s safety during his visit.

Protecting the Army’s senior officials became the mission of the Office of the Provost Marshal General in 1967, during the height of the Vietnam War. The “principals,” a term used by PSU agents to identify the people they protect, were the secretary and chief of staff of the Army. The protective service mission was assigned to the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command in 1971.

The mission expanded over the years, and today includes the protection of the secretary and deputy secretary of defense; the chairman and vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; the secretary, chief of staff and vice chief of staff of the Army; and their foreign counterparts when they are on official U.S. visits.

“The PSU’s mission is to protect these officials and their foreign counterparts from assassination, embarrassment, kidnapping or injury,” said CPT Tom Denzler, PSU commander.

The PSU operates much like the U.S. Secret Service, but with the specific goal of protecting Department of Defense leaders. The unit is, in fact, DOD’s premier provider of executive-protection services.

CW4 Bill Wiser, the PSU’s operations officer, said the unit is part of the 701st Military Police Group, at Fort Belvoir, Va. PSU often accomplishes its mission through cooperation with, or assistance from, the Army Criminal Investigation Command and its 6th, 202nd and 701st MP Groups, and agents from the Naval Criminal Investigative Service and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations.

Denzler also credits the National Guard and Reserve units that augment the unit.

“Since the horrific events of Sept. 11, 2001, our reliance on reserve-component soldiers has been incredible. We can’t accomplish our mission without them, because our workload has increased by threefold,” he said.

Agents from 11 different Army National Guard and Army Reserve units have augmented the PSU during the last 18 months. These agents, many of whom have a wealth of military and civilian law-enforcement expertise, arrive at the PSU and hit the ground running, Denzler added. “Their performance and motivation is a testament to the value of reserve-component CID agents.”

CW2 Randall Elrod, a Reservist from Boston, Mass., has been working with the PSU for 18 months.

“I was initially called up after Sept. 11, 2001, for one year and I’ve volunteered for a second year,” he said. “CID has really gone beyond the total Army concept by making this one big unit. The command ensures that active-duty and reserve-component soldiers are treated equally, and when soldiers deploy, their family matters have been taken care of.”

Before agents are assigned to the PSU, they must complete the CID Special Agent Course at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., and must have completed a one-year apprenticeship in the field.

“This gives an agent at least one challenging tour in the field,” said Wiser. “The unit has grown over the years, and there’s a good chance that if a soldier starts his career as a young agent, he’ll eventually be assigned here,” he added.

Wiser said not all agents begin their careers in the military police, but they should be specialists or above, 21 years old and have at least 60 semester hours of college credit to be considered for an assignment as an agent.

Once assigned to the unit, agents work as part of the Washington, D.C., Metro team.

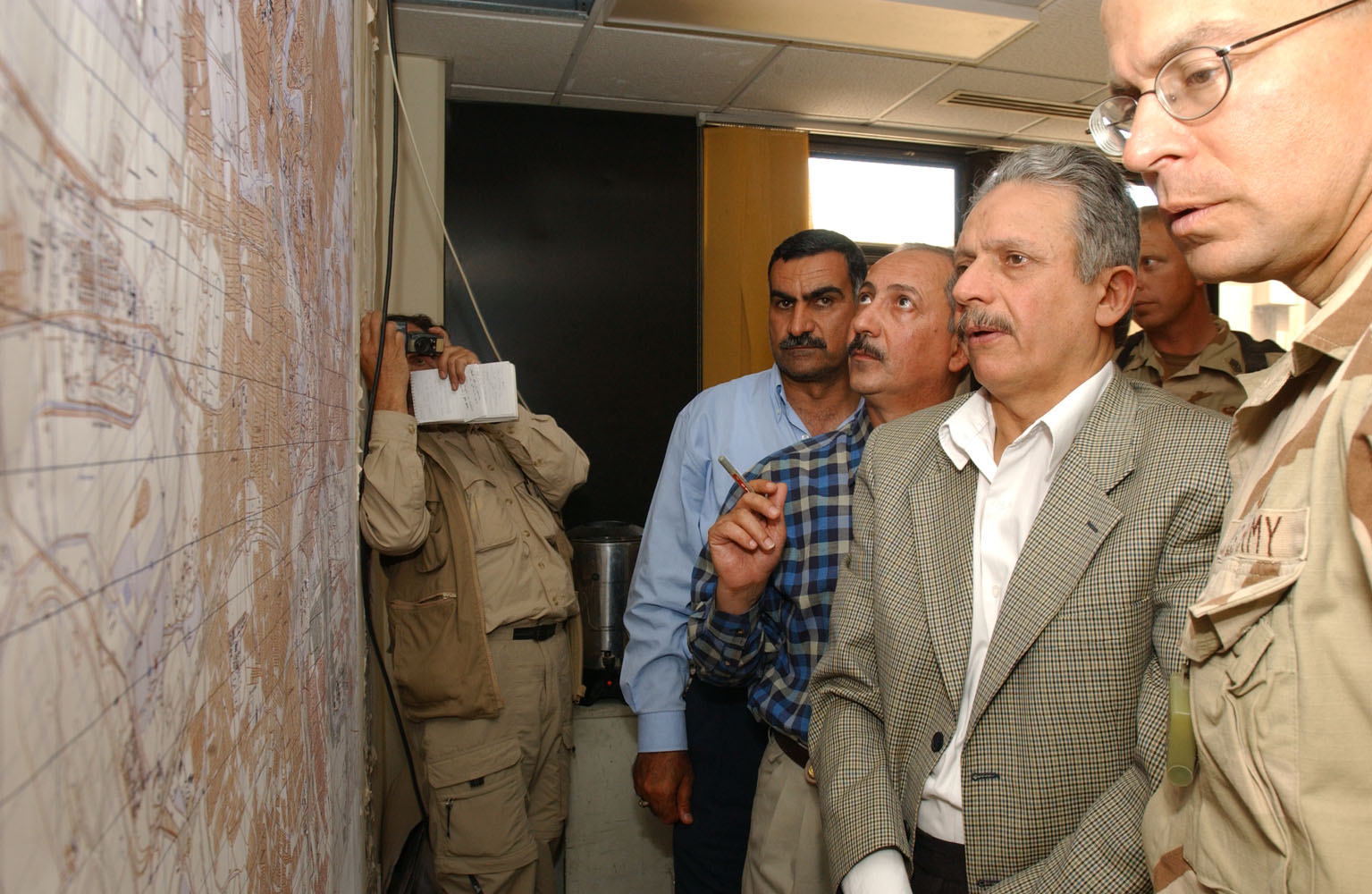

“Agents are assigned to the Metro team for about a year,” Denzler said. “They conduct residence watches, control-room operations, motorcade operations and close-in protection. Once they’ve reached a required proficiency level, they move to a travel team, providing protection overseas, often in a high-threat area, so the challenges are multiplied,” he added.

Some agents see the opportunity for travel as a plus. “In fiscal year 2002 our agents traveled to more than 40 countries. It takes a great deal of time and a number of agents to execute these missions, and we couldn’t do it without dedicated people,” Denzler said.

Overseas missions are coordinated with U.S. embassies and host-nation security officials, Wiser said.

“We work closely with the embassies overseas, since they’re able to facilitate mission success through their knowledge of the country and ability to provide liaison with other host-nation agencies,” he said. “For example, if we have a civilian principal, we may have local civilian police assistance, and military assistance for a military principal.”

As in any other military job, ongoing training is important for PSU agents.

“We send agents to several courses to equip them with a wide variety of skills,” Wiser said. “Some of the courses–such as protective services and evasive driving–are conducted at the Army Military Police School. We’ve also sent agents to courses offered by the Marine Corps and the FBI, and use some civilian companies for enhancement training in things such as marksmanship.”

Leave a Reply